![]()

![]()

Posted: September 5, 2008

|

(Nanowerk Spotlight) Several aspects determine how effective a pharmaceutical drug is. Probably the key issue is how well a drug molecule is able to reach its intended target. This need for target specific delivery of drugs has been well accepted in modern drug therapy. Many research efforts are geared towards improving not just the tissue accumulation, but also the cell-specific accumulation of drug molecules in the hope of improving the efficacy of these drug molecules. | |

|

The ability to target nanoparticles to specific types of cancer cells is one of the main reasons that nanoparticles have gained favor as a promising drug delivery vehicle. By increasing the amount of an anticancer agent that gets to tumor cells, as opposed to healthy cells, researchers hope to minimize the potential side effects of therapy while maximizing therapeutic response. Now, a group of scientists has taken this approach one step farther by targeting the specific location inside a tumor cell, where a cancer drug then exerts its cell-killing activity. | |

|

Volkmar Weissig, an Associate Professor of Pharmacology at the Midwestern University College of Pharmacy Glendale, explains to Nanowerk that efforts aiming at the development of pharmaceutical nanocarriers suited for the targeted delivery of biologically active agents to specific organs, tissues and cells date back to the late 70’s. Then, Gregory Gregoriadis discussed the enormous potential of liposomes as a colloidal drug and DNA delivery system for biomedical applications for the first time in two prescient papers published in 1976 in the New England Journal of Medicine – three decades before the term "nano" started replacing the term "colloidal" in the pharmaceutical literature. | |

|

During the 80’s and early 90’s, nowadays widely discussed problems and issues linked to the biomedical applications of nanoparticles such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, biodistribution, toxicity, surface modification, drug encapsulation, drug retention and release have been addressed and largely solved in the field of liposome technology, culminating 1995 in the marketing of Doxil® (liposomal encapsulated doxorubicin) as the first FDA approved nanomedicine. | |

|

However, despite the progress made in using nanocarriers to increase tissue accumulation of drug molecules to improve efficacy and to reduce unwanted side effects, the successful sub-cellular targeting of drugs specifically to cell organelles has only recently gained broader recognition. Many drugs have target sites inside the cell, at specific cell organelles or even inside organelles such as mitochondria or lysosomes. This means that for dramatically increasing the efficiency of such intra-cellularly acting drugs, they not only need to be delivered selectively to organs, tissues and cells, but also to targets inside cells, to cell organelles and even to the interior of cell organelles such as the mitochondrial matrix, which is surrounded by two cell membranes. The sub-cellular, organelle specific delivery of drugs has emerged as the new frontier for drug delivery. | |

| Diagram of a typical animal cell. Organelles are labelled as follows: 1. Nucleolus 2. Nucleus 3. Ribosome 4. Vesicle 5. Rough endoplasmic reticulum 6. Golgi apparatus (or "Golgi body") 7. Cytoskeleton 8. Smooth endoplasmic reticulum 9. Mitochondrion 10. Vacuole 11. Cytosol 12. Lysosome 13. Centriole (Image: Wikimedia Commons) | |

|

In a recent paper in Nano Letters ("Organelle-Targeted Nanocarriers: Specific Delivery of Liposomal Ceramide to Mitochondria Enhances Its Cytotoxicity in Vitro and in Vivo"), Weissig and his former colleagues from Northeastern University have clearly demonstrated that pharmaceutical nanocarriers can be targeted to subcellular compartments. | |

|

"These nanocarriers offer a significant benefit because they allow the specific delivery of drugs to subcellular targets without the need for chemical modification of the drug molecules" says Weissig. "Most importantly, we have shown that such organelle-specific drug-loaded nanocarriers can significantly enhance therapeutic effect. With suitable ligands, the strategy described in our recent paper could be applied to other organelle targets, thereby offering improved therapy for a number of diseases associated with organelle dysfunction." | |

|

Weissig"s team developed a lipid-based nanoparticle and decorated its surface with a molecule known as triphenylphosphonium cation, which is known to be taken up specifically by mitochondria, the cell"s energy-producing organelles. The investigators then loaded this nanoparticle with ceramide, a drug that forms holes in the mitochondrial membrane, which in turn triggers cell death by a process known as apoptosis. Ceramide also has been shown to work in concert with other anticancer agents to overcome the multiple drug resistance that develops in many tumors. | |

|

Using this formulation, Weissig and his colleagues observed that targeted cells – and only targeted cells – treated in culture accumulated ceramide in their mitochondria. Moreover, the scientists found that only the targeted nanoparticle was able to deliver ceramide to the mitochondria and trigger apoptosis. Untargeted nanoparticles loaded with ceramide, as well as free ceramide, did not accumulate in mitochondria, nor did they trigger apoptosis. | |

|

Weissig notes that an accidental discovery led him to start this work. | |

|

"In the Mid-90’s, as a Postdoc in Tom Rowe’s lab at the UF in Gainesville, I was screening drugs known to accumulate in mitochondria for their ability to inhibit a certain – at that time still putative – enzyme in Plasmodium falciparum, the causative agent of malaria. When trying to make a stock solution of such a drug, dequalinium chloride, I realized this drug is able to self-assemble into tiny small vesicles just like phospholipids form liposomes. In other words, by accident, I made what we would call today nanocarriers completely composed of molecules with high affinity for mitochondria, which in addition bear a positive surface charge." | |

|

Weissig named these vesicles, due to the lack of a better name, DQAsomes for "DeQAlinium derived liposome-like vesicles" (see: "DQAsomes: A Novel Potential Drug and Gene Delivery System Made from Dequalinium™"). | |

|

"Being well aware of the use of cationic liposomes for the delivery of DNA to the nucleus (as non-viral transfection vectors) it struck me that "my" DQAsomes might have the potential to deliver DNA to mitochondria" says Weissig. "The only problem I had at that time was the question as to why would anybody like to deliver DNA to mitochondria? Going back to the literature I quickly learned about breathtaking discoveries made just a few years earlier revealing the link between mutations of mitochondrial DNA and human diseases and with astonishment I read about the requirement for a mitochondria-specific transfection vector." | |

|

Weissig"s realization that his accidental discovery about the self-assembly of mitochondria-specific cationic molecules might actually meet this requirement totally changed the direction of his research and during the last 8 years he and his colleagues have demonstrated that DQAsomes do meet all requirements for mitochondria-targeted DNA delivery (see for instance: "DQAsome/DNA complexes release DNA upon contact with isolated mouse liver mitochondria" or "Mitochondrial leader sequence-plasmid DNA conjugates delivered into mammalian cells by DQAsomes co-localize with mitochondria" | |

| |

| Three levels of targeting cancer. (Image: Dr. Weissig) | |

|

Besides the application of DQAsomes – and similar mitochondria-targeted DNA delivery systems – as mitochondrial transfection vectors, a particularly intriguing aspect of this work involves the central role mitochondria play for apoptosis, i.e. programmed cell death. | |

|

Weissig points out that several clinically used and many experimental drugs are known to act directly on mitochondria in order to exert their apoptotic activity, i.e. to make the cell commit suicide. However, sufficiently high drug concentrations at the site of mitochondria usually require the administration of drug doses, which can easily reach toxic range. By selectively delivering such drugs to their intracellular target site, i.e. mitochondria, the drug dose can be reduced significantly. | |

|

In other words, sub-cellular, organelle-specific drug delivery may increase the therapeutic efficiency of a drug. | |

|

Furthermore, nanocarrier mediated mitochondria-specific delivery of pro-apoptotic drugs may even have two additional major effects, explains Weissig. | |

|

"First, cancer cells have developed the ability to avoid apoptosis by a variety of ways to "ignore" the body’s command to commit suicide for the benefit of the whole. The specific delivery of drugs known to trigger apoptosis via acting at mitochondrial target sites directly to tumor cell mitochondria, however, would literally bypass defective apoptotic mechanisms "upstream" of mitochondria and subsequently trigger apoptosis in tumor cells which otherwise would be resistant. | |

|

"Second, selective targeting to and selective release of drug molecules at their site of action, i.e. the surface of mitochondria, may constitute a novel strategy to bypass the p-glycoprotein, which resides in the cell membrane and which is one major cause for multi drug resistance. The carrier would literally hide the drug from the membrane-bound pump just like the Trojan Horse was hiding the warriors from the gate-keepers. " | |

|

The ultimate goal of research such as this one by Weissig is the design of nanocarriers, which combine all levels of drug targeting, upon systemic administration to specific organs, then to specific tissues, then to specific cells and subsequently to cell-organelles. | |

|

By Michael Berger. Copyright 2008 Nanowerk LLC |

![]()

Posted: September 4, 2008

|

(Nanowerk Spotlight) Borrowing from nature"s micro- and nanoscale propulsion systems, nanotechnology researchers have successfully used motor proteins to transport nanosized cargo in molecular sorting and nano-assembly devices (we just addressed aspects of this topic in our Nanowerk Spotlight from a few days ago – Nanotechnology transport systems get a closer look). In so-called gliding assays, surface-attached motors propel cytoskeletal filaments, which in turn transport a cargo. However, cargo and motors both attach to the filament lattice and will affect each other. While an effect of cargo loading on transport speed has been described before, it has never been explained very well. | |

|

To study this effect, scientists in Germany have observed single kinesin-1 molecules on streptavidin coated microtubules. They found that individual kinesin-1 motors frequently stopped upon encounters with attached streptavidin molecules. This work helps to understand the interactions of kinesin-1 and obstacles on the microtubule surface. An interesting, possibly even more important side result is that this understanding will not only help to optimize transport assays, balancing speed and cargo-loading, but can be used as a novel method for the detection of proteins as well. | |

|

"To understand what happens, we need to look at kinesin-1"s motor mechanism" Dr. Stefan Diez explains to Nanowerk. "Even though microtubules are made of ?13 protofilaments, it has been shown that kinesin-1 follows only one of them during one run and does not "switch lanes". Kinesin-1"s runs last for around 100 steps. This behavior makes an encounter of kinesin-1 and cargo on the microtubule surface highly likely." | |

| The speed of protein-coated microtubules gliding on a kinesin surface is determined by the density of the coating protein and can be used for differential detection. (Image: Diez group, Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics) | |

|

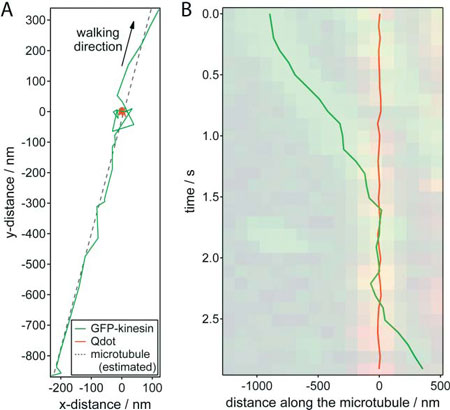

While there has been indirect evidence for kinesin-1"s stopping at roadblocks, Diez and his group were the first to directly show that kinesin-1 stops when it encounters an obstacle on the microtubule lattice. The Max Planck scientists were able to do this using quantum dots as roadblocks and particle tracking to follow single kinesin molecules stopping when they encounter these quantum dots. | |

|

Diez attributes the deceleration of cargo-laden microtubules in gliding assays to an obstruction of kinesin-1 paths on the microtubule lattice rather than to "frictional" cargo-surface interactions. This can be explained by kinesin’s particular properties: Kinesin moves in a hand-over-hand mechanism along a single protofilament. Its processivity requires the rear head to stay bound until the leading head is firmly attached to the next tubulin dimer along the protofilament. Therefore, says Diez, if a large molecule is blocking the next tubulin dimer, the leading head cannot bind and the rear head cannot detach. This situation effectively stalls the kinesin molecule. | |

|

"In a gliding assay, where each microtubule is transported by many kinesin motors, the stalling of some kinesin molecules causes a significantly increased drag force during the period of their attachment and provides an explanation for the slow-down of gliding microtubules." | |

| |

| Nanometer tracking of a typical encounter between a GFP-kinesin molecule and a quantum dot roadblock. (A) x-y trajectories of the GFP–kinesin molecule (green) and quantum dot (red).The microtubule position was estimated by linear regression of the GFP–kinesin data (dotted line). (B) Distance of the GFP–kinesin molecule and the quantum dot along the microtubule (relative to the average position of the quantum dot) plotted against time. The dual color kymograph, derived from the widefield TIRF imaging was put transparently in the background for comparison. (Reprinted with permission from Royal Society of Chemistry) | |

|

Together with his PhD student Till Korten, who first-authored the paper, Diez presents these new findings in Lab on a Chip ("Setting up roadblocks for kinesin-1: mechanism for the selective speed control of cargo carrying microtubules"). | |

|

Diez and Korten point out that a very intriguing aspect of their work is that – beyond an improved understanding of motor interactions with cargo-laden microtubules – this obstacle-caused slow-down of gliding microtubules could be applied in a novel molecular detection scheme. The way this would work is that the slow-down of cargo-carrying microtubules can be exploited to detect the binding of proteins to microtubules. Due to the small dimensions of microtubules, this method has the potential to be used for the detection of proteins in single cells. | |

|

"Using a mixture of two distinct microtubule populations that each bind a different kind of protein, the presence of these proteins can be detected via speed changes in the respective microtubule populations," says Diez. | |

|

Microtubule based transport has already been used to sort and to concentrate transported cargo. Diez and his group envision that these methods could be combined with their detection method to create highly integrated lab-on-a-chip devices. These devices would then be able to detect, sort and concentrate proteins from extremely small samples such as single cells. Further analysis such as mass spectroscopy could then serve to identify binding partners and modifications of the target proteins. | |

|

"Being extendable to the detection of many other proteins, this method has the potential to be operated with extremely small sample volumes and can be incorporated into highly-integrated, autonomously operating molecular sorting devices" says Diez. | |

|

By Michael Berger. Copyright 2008 Nanowerk LLC |

![]()

![]()

دوست داشتن از عشق برتر است. عشق یک جوشش کور است و پیوندی از سر نابینا یی اما دوست داشتن پیوندی خود آگاه و از روی بصیرت روشن و زلال. عشق بیشتر از غریزه آب می خورد و هر چه از غریزه سرزند بی ارزش است و دوست داشتن از روح طلوع می کند و تا هر جا که یک روح ارتفاع دارد، دوست داشتن نیز همگام با آن اوچ می یابد. عشق با شناسنامه بی ارتباط نیست و گذر فصل ها و عبور سال ها بر آن اثر می گذارد اما دوست داشتن در ورای سن و زمان و مزاج زندگی می کند و بر آشیانه ی بلندش روز و روزگار را دستی نیست.

عشق در هر رنگی و سطحی، با زیبایی محسوس، در نهان یا آشکار رابطه دارد . چنانچه شوپنهاور می گوید : " شما بیست سال به سن معشوقتان اضافه کنید آن گاه تأثیر مستقیم آن را بر روی احساستان مطالعه کنید."

عشق طوفانی است و متلاطم و بوقلمون صفت، اما دوست داشتن آرام و استوار وپر وقار و سرشار از نجابت. عشق با دوری و نزدیکی در نوسان است، اگر دوری به طول انجامد ضعیف می شود، اگر تماس دوام یابد به ابتذال می کشد و تنها با بیم و امید و تزلزل و اضطراب و " دیدار و پرهیز" زنده و نیرومند می ماند؛اما دوست داشتن با این حالات نا آشناست، دنیایش دنیای دیگری است. عشق جنون است و جنون چیزی جز خرابی و پریشانی فهمیدن و اندیشیدن نیست. اما دوست داشتن در اوج معراجش از سرحد عقل فراتر می رود و فهمیدن و اندیشیدن را نیز با خود می کند و با خود به قله ی بلند اشراق می برد. عشق زیبایی های دلخواه را در معشوق می آفریند و دوست داشتن زیبایی های دلخواه را در دوست می بیند و می یابد. عشق فریب بزرگ و قوی است و دوست داشتن یک صداقت راستین و صمیمی، بی انتها و مطلق.

عشق در دریا غرق شدن است و دوست داشتن در دریا شنا کردن. عشق بینایی را می گیرد و دوست داشتن می دهد. عشق همواره با شک آلوده است و دوست داشتن سراپا یقین است و شک ناپذیر. از عشق هر چه بیشتر می نوشیم سیراب تر می شویم و از دوست داشتن هر چه بیشتر تشنه تر. عشق هر چه دیرتر می پاید کهنه تر می شود و دوست داشتن نوتر. عشق نیرویی است در عاشق که او را به معشوق می کشاند و دوست داشتن جاذبه ای است در دوست که که دوست را به دوست می برد. عشق تملک معشوق است و دوست داشتن تشنگی محو شدن در دوست. عشق معشوق را گمنام می خواهد تا در انحصار او بماند، زیرا عشق جلوه ای از روح تاجرانه ی آدمی است. اما دوست داشتن دوست را محبوب می خواهد و می خواهد که همه ی دل ها آن چه را او دوست می دارد و آنچه را او از دوست در خود دارد، داشته باشد. عشق لذت جستن است و دوست داشتن پناه جستن. عشق غذا خوردن یک حریص گرسنه است و دوست داشتن همزبانی در سرزمین بیگانه یافتن.

عشق به سرعت به کینه و انتقام بدل می شود و آن هنگامی است که عاشق خود را میانه نمی بیند اما دوست داشتن را به آن سو راهی نیست.

" باید باشی و زندگی کنی که دوست داشتن از عشق برتر است و من هرگز خود را تا بلند ترین ترین قله های عشق پایین نخواهم آورد"

معلم شهید دکتر علی شریعتی

بازدیــــد امـــــروز : 189

بازدیــــــــد دیـــــــــروز : 206

بازدیـــــــــد کــــــــــل : 866201

تعـــــداد یادداشت هـــــــا : 2732

پاورپوینت درس 17 فارسی پایه یازدهم: خاموشی دریا

پاورپوینت درس 16 فارسی پایه یازدهم: قصه عینکم

دانلود پاورپوینت جنگ تحمیلی رژیم بعثی حاکم بر عراق علیه ایران در

دانلود پاورپوینت آرمان ها و دستاوردهای انقلاب اسلامی درس 25 تاری

پاورپوینت درس 9 فارسی پایه یازدهم: ذوق لطیف

پاورپوینت درس 8 فارسی پایه یازدهم: در کوی عاشقان

پاورپوینت درس 7 فارسی پایه یازدهم: باران محبت

پاورپوینت درس 6 فارسی پایه یازدهم: پرورده عشق

پاورپوینت علوم پنجم، درس11: بکارید و بخورید

پاورپوینت علوم سوم، درس4: اندازه گیری مواد

پاورپوینت درس 7 فارسی پایه اول دبستان

طرح درس و روش تدریس ریاضی ششم، فصل1: یادآوری عددنویسی

پاورپوینت نکات و سوالات هدیه های آسمان دوم، درس10: خانوادهی مهرب

دانلود طرح درس خوانا قرآن پایه ششم درس آب و آبادانی

طرح درس و روش تدریس ریاضی اول، تم 21: مهارت جمع چند عدد، ساعت و

[همه عناوین(2651)][عناوین آرشیوشده]